Don’t Assume “New” Hydraulic Oil Is Clean

Tags: contamination control

How uncomfortable is it for your organization when off-specification product moves through your quality-assurance process and reaches your customers?

I’ve heard of a few instances when this resulted in the termination of employees, management and even contracts. The issue here is that customers paid for a product they were unable to use. Does this sound familiar?

Likewise, when you purchase new lubricating oils, you are paying for a product that you cannot or should not put to immediate use.

What mystifies me is why so many people hold their lubricant suppliers to a different standard than they themselves are being held to as a vendor. Was there something wrong with the money you paid?

If not, why should there be anything wrong with the product you purchased? This question is especially important to ask yourself when it comes to hydraulic oil. Hydraulic equipment needs clean hydraulic fluid to operate efficiently and even safely. Contamination-induced problems like silt lock can cause hydraulic equipment to stick in place or behave erratically, leading to production problems and potentially severe injuries. Contamination, even an amount of dirt the size of a breath mint in a 40 gallon drum of oil, can severely impact the performance and expected service life of the hydraulic oil and the equipment itself.

That's why it is so important to test "new" oil, but especially hydraulic oil, when it arrives—before it goes into a machine. Some facilities take an even more proactive approach. Using separation systems that bring hydraulic oil to a highly clean state before it is ever put into equipment.

Demand Cleanliness

There are numerous reasons why new lubricants are dirty or off-specification. Contaminated drums or containers, cross-contamination of bulk loads and container mislabeling are just a few.

Humans are imperfect and make mistakes. Some suppliers are working diligently to improve their internal processes and minimize these issues.

Unfortunately, it is not enough, and to put it bluntly, that is our fault as lubricant consumers. Lubricant suppliers will respond to market demand. If we demand cleaner lubricants, they will provide them. Initially, the price will be higher, but as improved cleanliness becomes the norm, the price will stabilize.

It is up to you to perform a cost-benefit analysis and determine if the extra price per lubricant unit would be cheaper than the cost of filtration equipment, testing, man-hours expended to clean the oil or the cost of downtime and reduced reliability.

I would venture to guess that in nearly every case it is worth the extra expense. The first step in this process is to demand cleanliness.

How Lubricants Become Contaminated

In every manufacturing process, a certain amount of debris is produced. Much of this debris is small enough to become airborne and find its way into both the machinery and the product, whether that is cement, food, metal drums or other products.

Typically, the more inherently dirty the process, the laxer the cleanliness controls.

Crude oil extracted from the ground is filthy with particulate and other contaminants. As it progresses through the refining process, it becomes a “cleaner” fluid.

Obviously, some filtration occurs as part of the refining process, but the question becomes how much and to what degree.

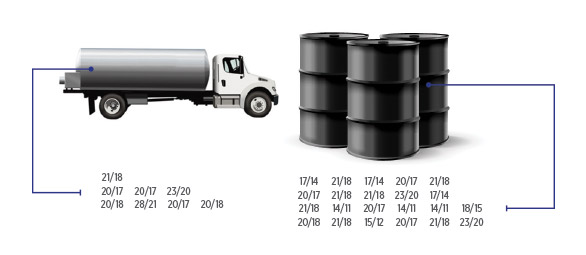

Even if the refinery was able to achieve and maintain a zero particulate ingression condition, the base oils are then loaded into railcars, tanker trucks or tanks aboard sea-going vessels, which is when things begin to go sideways.

What methods are used at this time to guard against particulate contamination? Keep in mind that we have not even begun to discuss water contamination or the cross-contamination of lubricants.

When the base oils are received at the blending plant, what cleanliness controls are in place? What is the strategy for breathers on the bulk oil storage tanks?

Don’t overlook additive cleanliness, as it doesn’t do any good to maintain clean base oils and then contaminate them with dirty additives.

Let’s assume your base oils are stored in a tank at the blending plant with questionable ingression methods, and the additives are also of questionable cleanliness.

Now they are mixed together in a blending vessel. How are these lubricants mixed? In small batches, this could involve something as simple as a paddle in a handheld electric drill. Was the container flushed with clean base oil? What about the mixer? Was it exposed to the environment? Is the blending vessel left open and exposed while mixing occurs?

For larger blends, how are they kept clean? Again, is there an acceptable particulate ingression strategy? Are the mixers flushed with a clean base oil? Are the vessels kept sealed to limit ingression? Some plants employ a “sparging” type of process to mix lubricants. What is the cleanliness of the air in use? Is dry instrument air utilized? What is the plant air like at your facility?

Once the lubricant is blended, is it filtered when it is put in its final packaging? What are the ingression prevention methods on the railcar, truck or tanks for the finished lubricant? For packaged lubricants, what is the cleanliness of the container? Drum manufacturing consists of grinding and welding, which not only creates metal particles but almost guarantees that particles will get into the drum or grease keg. For this reason, many companies request drums with liners.

What about plastic containers? What strategies are in place to ensure these containers are clean? Experts agree that you should filter the lubricant at every step in the process, from refining to final packaging. How can you ensure this occurs? You have little, if any, control over what happens to the lubricants before you receive them.

Hopefully, I’ve painted a picture of what can go wrong. I’m not implying that this is happening or that it will occur, but how can you be sure? Until you demand that your lubricants arrive in a clean, cool and dry state, it is unlikely to happen. Why would refineries and additive companies bother to keep the lubricant components clean?

Just like every other industry, there is pressure to keep costs down. Why should blending plants be concerned with filtering the oil, especially if you aren’t demanding it?

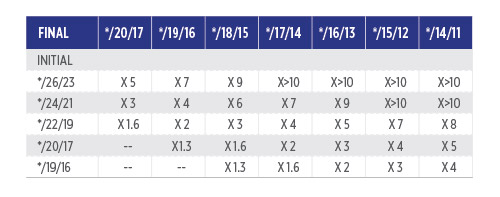

Potential life extension of hydraulic

systems when lubricant cleanliness is increased.

The Benefits of Cleaner Lubricants

I can almost guarantee that the oils you receive at your plant are several cleanliness codes dirtier than what you should be putting into your machines.

Cleaning your lubricants as little as one cleanliness code can provide a 35 percent increase in equipment life. How much is a 35 percent life extension worth to you and your organization?

Have you lost customers due to missed deliveries? Of those, how many were the direct result of a reliability- or downtime-related issue?

Some suppliers are working to provide cleaner lubricants. Those who are have said they are doing so in response to customers demanding it.

Several customers have even written their cleanliness requirements into their service agreement, which is a great idea.

Filter Before Use

I have yet to see a lubricant container from any supplier that states, “Filter before use.” You are responsible for this task, with all its associated costs.

I am encouraged that several of the plants I’ve visited are filtering their oils prior to use. Unfortunately, most of these facilities are filtering for a random amount of time.

For example, you might hear, “We hook up a cart and filter each drum for an hour before it goes into our tanks.” How do you know an hour is long enough or perhaps too long?

For the purposes of this article, filtering for “too long” will cost more in energy consumption and the time the technician spends babysitting the filter cart. You are unlikely to damage the oils by filtering them too long, but other activities could offer much more value.

What concerns me most is when oils aren’t filtered long enough, and dirty oil is put into the equipment. Without some type of particle counting, you can only guess as to how long your oils should be filtered.

Sadly, for every plant that is filtering its oils prior to use, there are untold numbers that are not.

The value of this simple improvement in your lubrication program cannot be overstated. The chart above shows the potential life extension of hydraulic systems when lubricant cleanliness is increased.

With few exceptions, oils should not be put into service without filtration. The length of time oil should be filtered will vary considerably based on the lubricant’s initial cleanliness level, the filter’s beta ratio and the gallon-per-minute rating of the pump on the filtration unit.

These results are from a study conducted a few years ago. Unfortunately, lubricant cleanliness has not progressed much across the board. Some companies are doing better, but there is still a long way to go.

Other Considerations

All of what has been described previously is related to just one aspect of the lubricant’s condition – its cleanliness. However, the moisture content, the possibility of lubricant cross-contamination, mislabeled lubricants and off-specification lubricants must be considered as well.

How often would you visit a restaurant that continues to mess up your order? How long are you willing to sit in a restaurant and wait for your order? How many times will you accept the answer that it’s coming or that it will be right out before you get up and leave, likely never to return?

Do you think your customers are any different? How often can you get away with missing delivery dates? How many of those missed deliveries are due to equipment failure? The majority of those failures could be traced back to equipment wear and particle-induced failure.

Remember, new oil does not mean clean oil. There are countless companies out there, including your competitors. While it may sound implausible, lubricant cleanliness can in some cases be a true competitive advantage, especially if you are taking a proactive approach that maintains both your hydraulic lubricants and machines in a highly clean state through oil regeneration or other clean technologies.